Sökandebanken

- Arbetsförmedling på distans

Short paper for STIMDI¹98 (24-26 August)

Richard Whitehand, Nomos Management AB

Introduction

Sökandebanken is an application developed by AMS (The Swedish Labour Market Board), to provide a Web-based recruitment service. It enables job seekers to register information in a database - their qualifications, experience and other factors of interest to possible employers. Employers can use the service to create a candidate profile for a vacancy they are trying to fill, and then use this profile to search the database for suitable people.

Sökandebanken is one of a series of Swedish Web-based employment/recruitment applications provided by AMS, accessed by using the URL: http://jobb.amv.se

The development of Sökandebanken followed a user-centred design process, which may be one of the key reasons to its success. Despite relatively high functionality when compared to other typical internet-based applications (online shopping, internet banking, etc), usability tests have shown that even job seekers who are relatively novice Web users can quickly learn to use the application and expose themselves to online recruiters. Currently there are 4000 employers and 50 000 job seekers registered in Sökandebanken, and each day up to 100 employers and 2500 job seekers use the service - figures which tower over those of competing systems that exist in Sweden.

This short paper gives an overview of the user-centred design process that was used in the development of Sökandebanken versions 1 and 2. (At the time of writing, version 1 is that currently available on the Internet which has been running with full public access since April 1997, and version 2 is about to be launched). The different user-centred design activities that were carried out during development are briefly described together with the benefits they had for the development as a whole.

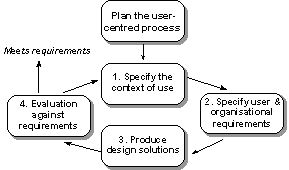

The rest of this paper broadly follows the 4 main stages of the user-centred design process as set out in the draft international standard ISO 13407 - "Human-centred design processes for interactive systems". (A brief summary of the rationale and principles of user-centred design is given as an appendix for readers who are unfamiliar with the standard).

From ISO/DIS 13407 - "Human-centred design processes for interactive systems"

1. Specifying the context of use

AMS has a comprehensive internal system for supporting the staff of their national network of employment offices. Several of the Sökandebanken project members were familiar with this system and the way in which registered job vacancies could be matched with suitable job seekers. Having worked in employment offices, they were also familiar with the characteristics and needs of job seekers. However, much of this knowledge was not documented and thus not readily available to the project team as a whole. In addition, little was known about those people recruiting job seekers and how they might use a Web-based service.

In order to address these issues a context analysis was carried out, including a structured 'focus group' meeting with a representative group of employers. This resulted in the documentation of key knowledge held by individuals, and essential background information obtained from the focus group work, including:

- An overview of how employers carry out recruitment.

- Job seeker and employer knowledge, skills and experience.

- Technological issues (job seeker and employer access to the Internet, hardware and software used, etc).

- Identification of the main tasks likely to be carried out using the system.

2. Defining requirements

The next stage was to define the functional requirements of the system. In defining requirements at this stage care was taken not to specify any specific implementation form as a requirement. The necessary information required for the job matching process was defined, together with identifying those functions needed to support the user tasks of entering and searching this information. Possible interface designs were not discussed.

This approach to requirements definition had several advantages:

- Concentration on WHAT (user tasks) and not HOW (interface implementation) meant a focus on properly establishing and understanding the purpose and usage of the service before 'jumping in' to what it might look like, thus no untried interface design details were set prematurely as a "requirements" which might then need to change.

- Clear and very concise reference for system functional requirements.

3. Design

Interface design work began with brainstorming with whiteboard and very basic paper prototypes of several different design concepts (working from the context and functional requirements specified earlier). Early "walkthroughs" of these concepts were carried out by people within the project team and also any individuals less involved in the development who were readily available. These quickly indicated the best design concept in terms of task suitability, overall complexity and intuitiveness.

The chosen concept was then prototyped further on paper and then simple HTML pages. The design was developed iteratively with reviews followed by improvements and the addition of further functional detail. The resulting prototypes gave a clear picture of how different functions could be implemented, and how user tasks would be carried out with the system. However, in terms of graphic appearance these "function and flow" prototypes were quite some way from being a finished design, and all data was static.

After this period of iterative prototype development, the major programming and graphic design work began. The creation of the prototype prior to this work meant that the programmers could concentrate on real program implementation issues and the graphic designers could focus on appearance detail - the "what happens next" and "how do they do this" questions were already dealt with.

The programming and graphic design work resulted in a fully operational prototype (working with a 'live' database) which could then be tested more formally with users. After usability testing, further improvements to the interface design were implemented prior to launch.

This approach to the design work meant that:

- Interface design was kept "on track" by rapid feedback through the design process.

- The expensive and time consuming programming and graphic design work could be carried out directly without 'stoppages' concerning issues of interface functionality and flow. There was no unnecessary 'throwing ' of work due to unexpected or changing requirements

4. Evaluation

Usability evaluations were carried out throughout the development process, although varied significantly in their nature.

Early during development, competitor web employment services in Sweden and abroad were reviewed as an input to design ideas, and to raise awareness of problems to avoid. Expert reviews of initial design sketches/prototypes provided quick and efficient feedback into the process, as did short 'participatory' evaluations carried out by experts working with users on slightly later prototypes.

Usability laboratory testing of fully operational prototypes was carried out later. Tests were run with two groups of representative users - employers and job seekers - both groups ranging in experience of using the web. This division was important as whilst there were similarities between the interface content for the different users, task demands were quite different (job seekers could spend time learning the system and creating a presentation of themselves, whereas recruiters who would be using this system as part of their work required fast and efficient results). The tests gave detailed feedback about actual user performance with the interface, their subjective assessment, and lists of specific interface details that could be improved.

Finally, after launching the service, an online subjective questionnaire was used to measure real user satisfaction, identify possible areas for further improvement, and new user requirements that might be addressed in later versions.

Concluding remarks

Sökandebanken is one example of a successful project developed using a user-centred design process. The project was successful in two key respects:

- A usable product was produced, with the correct functions for the intended users and their tasks.

- A successful development process which, whilst not totally problem-free, met the requirements defined at the start of the project and incurred no large re-working costs or long delays.

The Standish Group (USA) surveyed IT executive managers in 1995 to research the number of successful and unsuccessful IT development projects and the reasons for their success or failure. The results (available on the web at http://www.standishgroup.com/chaos.html) were remarkable:

- 16.2% of projects fully succeeded (Met their schedule, on budget, to initial requirements)

- 52.7% of projects were challenged (Delayed and/or over budget, and not meeting all initial requirements).

- 31.1% of projects were cancelled at some point during development.

Top 3 success factors

| Top 3 challenge factors

| Top 3 failure factors

|

Thus it is not difficult to see how the activities carried out in the Sökandebanken project, and other projects using a user-centred design process, can have a very significant role to play in streamlining the development process and limiting cost overruns, quite apart from the benefits of improved product ease of use.

The development team (Main members and their roles)

- Arbetsmarknadsstyrelsen:

- Gunnar Wass - Project leader

- Nomos Management:

- Mats Lind - Context & Requirements work

Richard Whitehand - Prototyping & usability reviews

Nigel Claridge - Usability lab testing - AU System:

- Jan-Erik Öhman - Programming team leader

Daniel Larsson - Graphic designer

Appendix : User-centred design and ISO 13407

There are numerous methods to support the design and evaluation of software, most focus on meeting the technical and functional requirements for the products. This is of course important, however, it is equally important to consider usability requirements if the product is to be successful. The draft international standard ISO 13407 - "Human-centred design processes for interactive systems" sets out four main principles for user-centred design:

1. An appropriate allocation of function between user and system

Determining which aspects of a job or task should be handled by people and which can be handled by software and hardware is of critical importance. This division of labour should be based on an appreciation of human capabilities, and their limitations, as well as a thorough grasp of the particular demands of the task.

2. The active involvement of users

The extent of user involvement depends on the precise nature of the design activities but generally speaking the strategy is to utilise people who have real insight into the context in which an application will be used.

3. Iteration of design solutions

Iterative software design entails the feedback of end-users following their use of early design solutions. These may range from simple paper mock-ups of screen layouts to prototypes with greater fidelity which run on computers. The users attempt to accomplish 'real world' tasks using the prototype and the feedback from the exercise is used to develop the design further.

4. Multi-disciplinary design teams

User-centred development is a collaborative process which benefits from the active involvement of various parties. It is important that the development team has a good balance of those people who have relevant insights and expertise (not just the programmers and system developers!).

ISO 13407 also sets out four essential user-centred design activities which should be planned for and undertaken in order to incorporate usability requirements into the development process, and iterated until these requirements have been met. A plan should identify how these activities can be integrated with other development activities, as well as people responsible for them.

- Understand and specify the context of use

- Specify the user and organisational requirements

- Produce design solutions

- Evaluate designs against requirements